- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Writing academy unites refugees with a shared passion

Listen to this article:

While Belgium has a variety of organisations that assist refugees, this is usually to help them with basic needs: food, shelter, medical care. Once those are taken care of, there are few opportunities for these newcomers to pick up interests they once had.

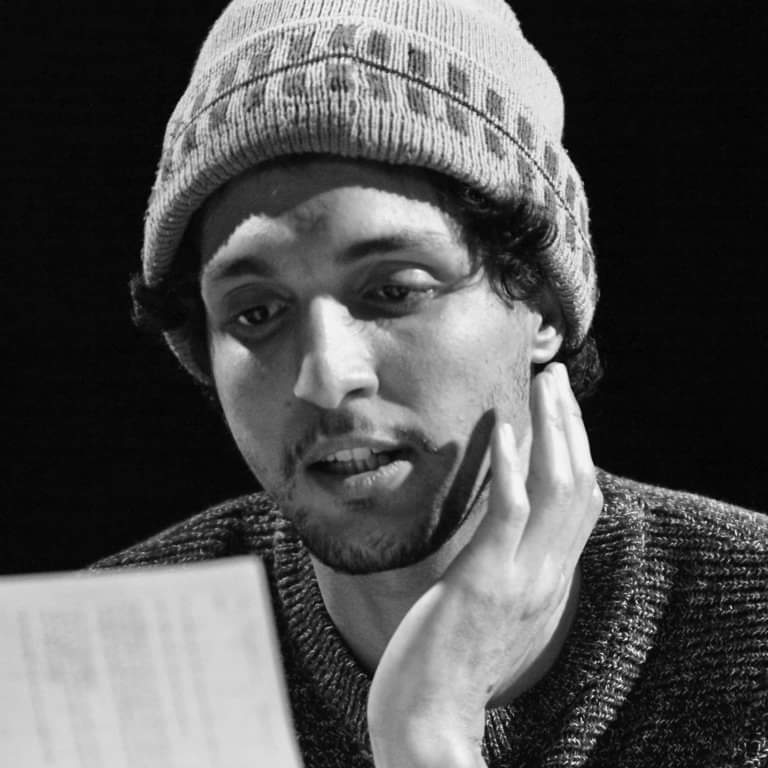

That’s why Sulaiman Addonia (pictured above) founded the Refugee Writing Academy. No one knows better than he the ways in which the refugee experiences is fraught with obstacles to leading a normal life.

“I founded the academy because I’m a refugee,” he says. “I know from experience how traumatising it is coming to a new country, learning a new language, a new culture. I wish I had had the opportunity to go to a place where I could express myself.”

Novelist Addonia landed in Brussels 11 years ago after arriving in London via Saudi Arabia, Sudan and his homeland of Eritrea. “My father is Ethiopian, my mother is Eritrean,” he says. “They came from countries that were fighting each other, and they fell in love. They got married. Both sets of parents were not happy about the relationship, but to me it speaks a lot about love and how it transcends war and nationalism.”

Intellectual needs

Both of Addonia’s well-received books – The Consequences of Love and Silence is My Mother Tongue – have their roots in this story. “I never lived with them. My father was murdered when I was two, and my mum left when I was three. The memory that lingers is this love story. That is what motivates me in life – love, books, literature and art.”

Following the death of his father, Addonia’s family fled to a refugee camp in Sudan. His mother soon left to work in Saudi Arabia, and he and his brother stayed in the camp with his grandmother.

Addonia eventually went to Saudi Arabia and from there to the UK. While his basic needs were met there, his intellectual and emotional needs were not. He couldn’t find an outlet for his interests and creativity. He wanted to start a group where refugees who were interested in books and writing could come together. “I went around to different organisations, but I never got any support.”

After meeting his Belgian partner, he settled in Brussels – where he found the support he was looking for from the municipality of Ixelles. While they don’t offer him riches, they offer him a space. That was enough. He put out the word to refugee organisations across Belgium, and applications began to come in.

“I don’t like the term ‘the voice for the voiceless’,” Addonia says. “Everyone has their own voice. What they need is a place to express that voice.” Newcomers responded to that idea. “People were commuting three hours to get here. I had one student who came all the way from Luxembourg province, saying ‘I want to write’. He stayed with relatives and slept on their couch.”

A chance to share

Besides Addonia, several tutors volunteer to run the courses. “Some of the participants have better skills than others, but we try to respond to that,” he explains. “We also don’t want language to be an obstacle, so I make sure that all the tutors speak more than one language.”

English, Dutch and French are always an option, as is Arabic, Addonia’s native tongue. “In the last class, we had a tutor who spoke Italian and Somali, for instance. So this way we can address multiple languages.”

Many of the participants speak English, which helps them communicate with each other. For Muhned Bnana, being able to share his experience was as valuable to him as improving his writing skills. “Discussions, listening to others, sharing thoughts in general, and of course, the appreciation that others gave me when I shared a text” were what he appreciated most about the academy, he says. “It gives meaning and value to what I do.”

Bnana left Libya in 2017 “to escape war and chaos” and now lives in Ghent. He has participated in the academy twice. “I love literature and writing in general, so it was an opportunity to do what I like, and also to make new friends who share the same passion.”

He was a regular contributor to magazines in Libya and North Africa, writing about history, identity and culture. He applied to the Refugee Writing Academy to learn how to transfer those skills to short story writing. It served him well, he says, teaching him how “to migrate from non-fiction writing, which is based on information, to fiction, which is more based on emotions”.

A voice, a story

Participants in the academy can write whatever they want, Addonia explains. “Everyone chooses a subject they want to talk about. We give them some basics about writing, but mostly we just support them.”

While refugees are the main target group, some of the participants are simply newcomers who are intrigued by the opportunity to share their work with fellow foreigners. Quỳnh Iris de Prelle, for instance, has lived in Brussels for several years. She wrote screenplays, poems and articles in her native Vietnam. “But I wanted to take part in a course here, where I live,” she says. “I wanted to meet new people and learn more about writers from different countries, and I wanted to learn to write in English and French.”

She also took part in the academy twice and also wanted to transfer the skills she had to another form of writing. “I learned so much from Sulaiman and from the others, who all have completely different styles and stories. It requires patience to write a story or a novel, which is completely different for me than when I write poetry. The course helped me to use my memories and posed questions like: What is your voice? What is your story?”

A writer, not a refugee

Coming from somewhere else is what connects them, but the participants are vastly diverse. “Each one has their own experience,” says Bnana. “But we share a common goal, which is to put down our ideas, feelings and experiences on paper.”

Last year, Addonia was able to put together an extra course with the support of Brussels literary house Passa Porta. “I then persuaded them to give one of my students a two-week residency. He told me that being in that programme was the only time he didn’t feel like a refugee but like a writer. That’s really important. The more refugees I work with, the more I realise how important it is.”

Addonia hopes that other municipalities will start similar programmes for newcomers. “We need something like this everywhere.”

This article is part of The Bulletin's digital magazine. Top photo (c) Bart Dewaele

About the author

Lisa Bradshaw is the editor-in-chief of Flanders Today, The Bulletin’s sister publication, and a daily contributor to The Bulletin. She also contributes to Ackroyd Publications’ other titles, including WAB and Expat Time. She has worked as an editor, proofreader and writer for other publications and organisations in Belgium and the UK, including Flanders Audiovisual Fund, Metropolitan, European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy and Ghent University. Previous to her arrival in Belgium, she served as the arts editor for an alternative weekly in the US.

Comments

What a lovely idea, to inspire writers in the local community and beyond.