- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

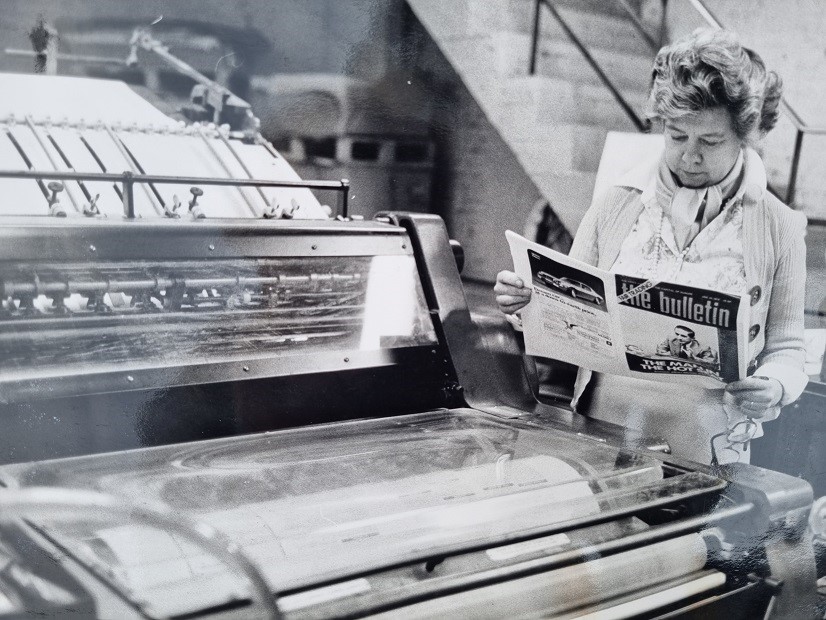

The Bulletin at 60: From the archive (September 2002): Guts for survival, charm for success

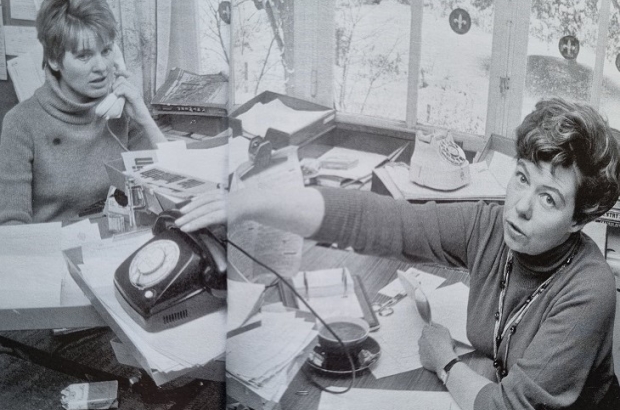

Founder of The Bulletin Monique Ackroyd tells Brigid Grauman about the magazine’s early days – and recalls some memorable parties

With clockwork regularity, newspaper clippings – sometimes torn, sometimes cut out with scissors, but invariably annotated with green ink – make their way to the editorial and advertising departments of The Bulletin.

We all know who they come from. They are a reminder that though long retired, Monique Ackroyd, OBE and The Bulletin’s founder, is not dropping her guard.

She handed over management of Ackroyd Publications to her son, John Stuyck in 1986, but Monique, 77, still reads every word of the magazine after it is published and keeps an eagle eye on the local press for stories of interest or for possible new advertisers.

Nowadays, Monique shares her time between an apartment in Uccle and the priory she converted into an art gallery in a village on the North Yorkshire Moors. But, she admits, it’s been a wrench to withdraw from the magazine. “I miss it terribly,” she says. She paints, mostly flowers and landscapes, and confesses to doing quite a brisk trade in her own work.

She started at The Bulletin in the cellar of her house in Rue des Glaieuls, in 1962, the year her father, Colonel Edward Ackroyd, died. A Yorkshireman, he had settled in Brussels after World War One, marrying Monique’s Belgian mother and setting up an advertising agency. He cut a dashing figure on the local British scene with his dimpled chin and his fondness for Saville Row suits and natty bowler hats. He was involved with the Toc H Talbot House, the social service founded after World War One for ex-servicemen, and published the Belgian British Bulletin (BBB), a parish pump newsletter for the Brits.

Monique spent World War Two in England, with her sister and mother, and after stints at the Yorkshire Post and the Daily Express, she decided in 1947 to come home. She doesn’t have much time for those she calls the Old Guard of the British community, and entirely credits Brussels’ American expatriates with the Bulletin’s successful take-off. “The Americans launched us. They were the ones who bought us and subscribed.” It was with some relief that she saw a new guard of Britons move to Brussels when the UK joined the Common Market.

Those early days were not easy. “I had no money, and the banks weren’t lending.” So she went knocking on the doors of her father’s former clients who were prepared to put ads into the first issues. They included Delhaize le Lion, Austin cars , Fourcroy, Vat 69 and Sarma. She shared the Salvation Army’s printing presses and got two local journalists on board, Will Reckman and Jan Heyn. Her partner Danny De Laet printed out subscription addresses on a roneo machine.

Monique went on getting all the ads in herself until she could afford to hire staff. For many years after that, she’d still pick up the phone and in her inimitably bossy yet flirtatious style would clinch a difficult deal. “No paper can live from sales alone,” she says. “It’s got to be the ads, unless it’s outside help like a bank or a political party.”

When there weren’t enough small ads she’s occasionally stoop to making them up to swell the section that eventually developed into one of the magazine’s most lucrative. Legend has it that for a while, she fed her three children only baked potato for supper. At any rate, she was able to pride herself on being that rarity – the owner of an entirely independent publication.

It might seem far-fetched to call Monique a feminist, yet she had a track record for hiring women, starting with my mother Aislinn Dulanty in 1967. Aislinn was a feminist, and a crusader for the rights of all underdogs. She stamped her strong and witty personality on the magazine, and increased Monique’s very small stable of writers to one that has included, some of the top journalists in Brussels. Many a young FT journalist contributed to The Bulletin in the days when they wore fitted shirts and long hair. In fact, most foreign correspondents who’ve spent any time in Brussels can be counted among its contributors.

Aislinn and Monique made a vibrant if edgy team. Grudging admiration on both sides was one hallmark of their relationship, and their arguments were legendary. There was never a dull moment at The Bulletin. Cleveland Moffett, deputy editor for many years, describes it as “a permanent soap opera”.

After Monique’s cellar, The Bulletin moved to her new home in Uccle’s Dieweg. Later, she fulfilled an old dream and rented a floor in the Sablon, above the Vieux Saint Martin café/restaurant. Although she claims she doesn’t remember it, there was a serving-hatch in the wall between her office and the main editorial room. When she had something to say, Monique would whip up the hatch, stick her head out the hole and shout her message through as though she was in a puppet theatre.

Other offices followed as The Bulletin expanded, first in Rue des Minimes, then Avenue Louise, Avenue Molière, and in the most recent move in 1997 to Chaussée de Waterloo. Much more dramatic than these moves were some of The Bulletin’s yearly jamborees for its advertisers. “We needed to entertain but I couldn’t afford to offer trips to the Bahamas. On one occasion, I flew clients to England for a day at Beaulieu Abbey because Sabena owed me so much money that they gave me free tickets.”

The most memorable of these parties took place at Beersel chateau with a gaggle of Gilles de Binche among the entertainers. A clever idea for renting the Egmont Park behind the Hilton Hotel turned into a disaster when it poured with rain and women’s high heels sank deeper into the mud, while the Hilton’s manager handed out plastic rubbish bags for head protection. “I’d told him,” says Monique with a coquettish twinkle, “that it never rains when I give a party.”

Perhaps chutzpah is what best sums up Monique Ackroyd (pictured above). Love her or not, no one could ever accuse her of being chicken. “I had to make the Bulletin work,” she says.