- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Dying with dignity: The story of euthanasia in Belgium

Listen to this article:

Belgium’s euthanasia law has made international headlines over the years, not least when it was passed in 2002. It was only the second country in the world to legalise the procedure, after the Netherlands. Then in 2014, it became the first – and remains the only – country in the world to allow euthanasia for those under the age of 18.

While this has created a reputation for Belgium as a pioneer in death with dignity, it all happened by political accident. In 1999, the dioxin feedstock contamination crisis caused a revolution at the ballot box, and Belgium’s Christian-democrats – CD&V and cdH – lost their normally comfortable lead in the federal elections. For the first time in more than 50 years, Belgium had a government coalition without the moderate-right Christian-democrats.

“The government coalition was made up of the socialists, the liberals and the green parties, and they decided to take a look at all of the cases that involved ethics – those that were untouchable under CD&V,” explains Dr Wim Distelmans. “And that’s the reason why the euthanasia law was eventually passed. Ask people in other countries, like Germany and France, if they’d like to see euthanasia legalised, and they’ll say yes. But the political agenda is against it.”

Under strict conditions

Distelmans is an oncologist and palliative care specialist at UZ Brussel, the hospital associated with Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). He is also a professor of end-of-life care at VUB, which was the first institution in Belgium to create a team specialised in palliative medicine. Team Omega was launched in 1988 and still exists today.

Distelmans is the chair of Omega and was also instrumental in getting Belgium’s euthanasia law written, debated and passed. Since the law came into force, more than 22,000 people in Belgium have chosen to die by euthanasia.

The number of people requesting the procedure – which is administered orally as a drink or with an IV – goes up every year, a testament, says Distelmans to people becoming more aware of their right to choose when and how to die. Currently 2% of all deaths in Belgium are by euthanasia.

That said, the regulations around the procedure are extremely strict. Four basic conditions must be met:

- the patient must be mentally competent to make the decision;

- the patient must request euthanasia on two separate occasions, in writing;

- the patient must be suffering from the effects of an incurable disease or mental illness, and all treatment options must have been exhausted;

- the patient must be experiencing unbearable suffering from the illness, either physically or psychologically.

The medical community must ensure that all of those criteria are met as well as confirm there has been no pressure put on the patient by family or anyone else. Besides the patient’s physician, a second physician who is independent from the patient must approve the request. In the case of mental illness, a psychiatrist must also sign off on it.

“It took six years to write this law. We struggled over every word, every comma,” says Dominque Bron, also an oncologist who has been president of the ethics committee at the Jules Bordet cancer institute in Brussels for 20 years. She was also involved in writing the law and the political debates that followed. “This law is really excellent from a practical point of view. Now, 18 years on, we can be confident that there are many options for patients – from those who are facing death to those with neurological problems. For me, the law is just perfect.”

Sigh of relief

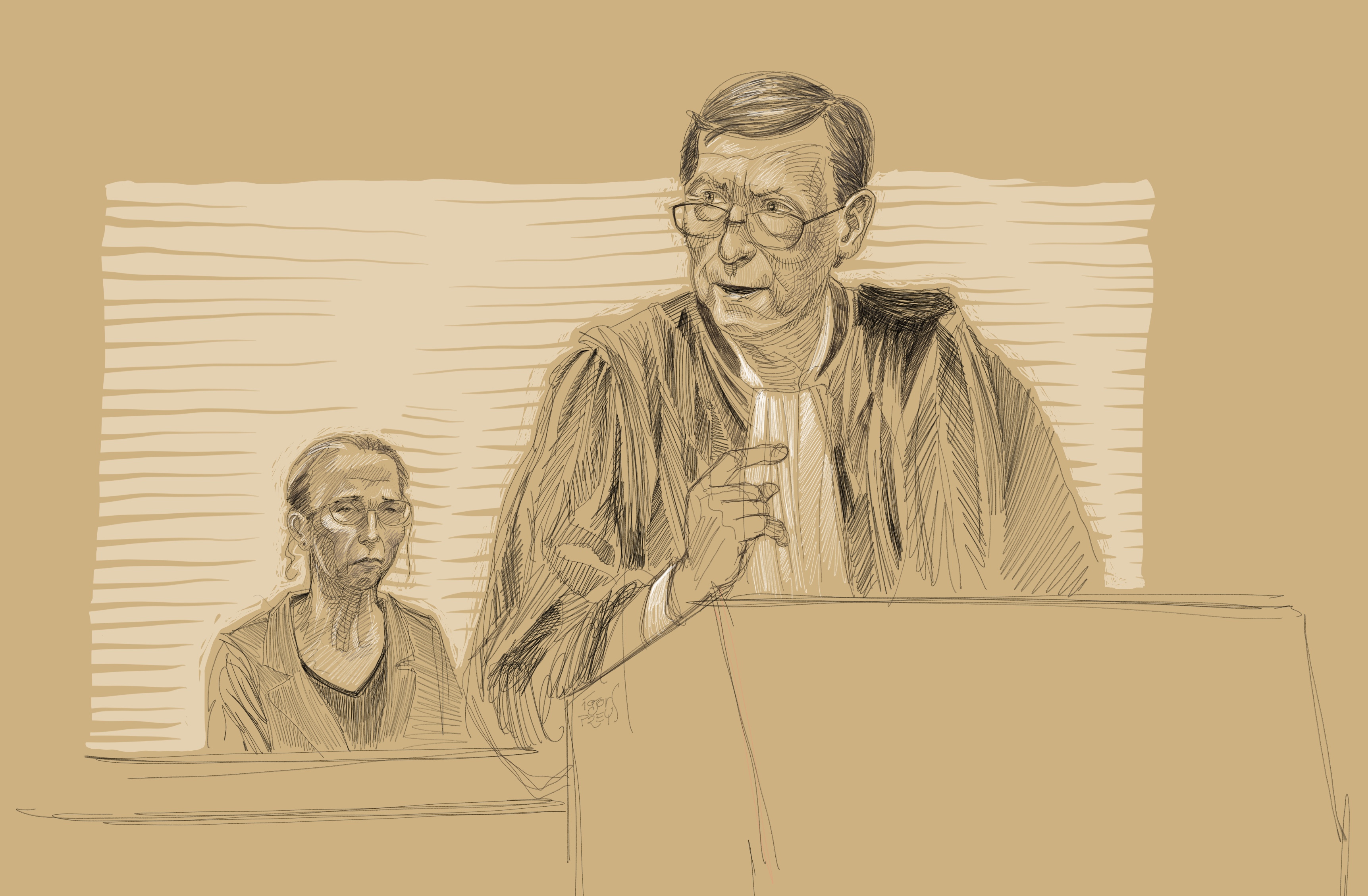

Not everyone feels that way, as evidenced earlier this year in Ghent, when the euthanasia law was challenged in criminal court for the first time. In what became a media circus and polarised opinions on both sides of the debate, three siblings accused three doctors of murdering their sister. Tine Nys had received euthanasia in 2010 for what she and her doctors described as intense suffering caused by an incurable psychiatric illness. She was 38.

During the trial, the family suddenly dropped charges against their sister’s own physician. The other two were acquitted by the jury, which found that they had followed all the legal requirements.

Belgium’s medical community breathed a sigh of relief, concerned that if doctors and psychiatrists actually went to jail they would be hesitant to approve euthanasia in future. “The doctors were acquitted because there was no breach to the law,” explains Bron. “The problem was that the family didn’t know that their sister had made this decision. They simply didn’t want her to have euthanasia. But the law is clear: It’s not up to the relatives.”

Nightmare situations

While survey after survey shows that a large majority of Belgians support the euthanasia law, the right to the procedure based on psychological suffering feels more murky than a straightforward terminal illness. And in fact, regardless of whether the illness is physical or mental, it does not have to be terminal. It simply has to be unbearable and untreatable.

The law was written the way it was so that severe psychiatric disorders would be on the same playing field as physical illnesses. “This isn’t just depression we’re talking about,” says Bron (pictured below). “It’s a loss of autonomy. It’s something that cannot be controlled with medication. These are nightmare situations for the patient and for the patient’s family.”

Dr Dominque Bron

Dr Dominque Bron

There is also a federal euthanasia commission that reviews every euthanasia file. After the procedure is carried out, the file goes to the committee, of which Distelmans is chair. “If a doctor forgets to fill in the date of birth or date of death – these are technical errors,” says Distelmans. “We can still judge that the file is acceptable if the four basic conditions are met.”

And if they are not? “Then it must be investigated with the family and with the doctor,” explains Bron. “This can even be taken to the courts. But it’s very, very rare. I have seen maybe two or three situations like this in 18 years.”

That’s because, she says, doctors are extremely careful when it comes to administering euthanasia, often turning to colleagues for advice if they themselves have never approved the procedure before. “Doctors really don’t want to get this file back.”

Speeding up death

There is a huge difference in the number of euthanasia procedures carried out per region. A full 80% are administered in Flanders and Dutch-speaking Brussels. “We don’t know why,” says Distelmans, “but it’s high time a study was carried out.”

There is of course a theory. “We think that French-speaking doctors do many more palliative sedations,” he says. While euthanasia is the deliberate ending of someone’s life at their request, palliative sedation means putting them in a medically induced coma. In the case of an accident or brain haemorrhage, for instance, doctors can make the decision themselves to induce a coma.

“Because the patient has not specifically given permission, it’s not euthanasia,” explains Distelmans. “But there is a lot of debate around this. I’m convinced that if a patient is put in a medically induced coma, it does speed up death.” This is how many countries get around the lack of a euthanasia law, including the United States and France.

Medical specialists are now trying to get the euthanasia law adapted to allow permission to be given ahead of time. “Currently, people can register a living will that directs doctors to administer euthanasia if they are not capable of asking for it. So you can say, ‘if I’m in a car accident, and I’ve been in a coma for months, I give permission to end my life through euthanasia’.”

But you cannot do that if a coma is not involved. “People want to create a living will in the early stages of dementia, or in case of another condition, like a brain tumour, for instance, so that they can say that if they are no longer capable of making the decision – we call this acquired incompetence –they want to receive euthanasia.”

A petition by information forum Leif to add this to the euthanasia law has already been signed by more than 75,000 people, he says, “including many politicians”.

A death of one’s own

According to Bron, 90% of people who are told they are going to die of their illness refuse to accept it. About 9% want to talk about palliative care, and the rest ask for euthanasia.

The will to live is strong at any age, and this lends to a denial of the inevitable. But there is also an unwillingness to talk about death within the larger community. It’s still a taboo subject. This is slowly changing, however, because of the euthanasia law but also because of W.E.M.M.E.L, an expertise centre on end-of-life options. Launched by Distelmans and UZ Brussel, it houses six organisations, including Omega, Leif and day centre Topaz.

Topaz is a place where anyone can go who is faced with a terminal illness. They can meet other people, have lunch, take part in activities and support groups, or just sit quietly if they wish. The idea is that they do not face the end of their lives alone. The subject of death isn’t taboo at Topaz; instead it’s what connects people.

Topaz and the other organisations are based in Wemmel, just over the border with Brussels, but because there’s nothing like it in the other regions, the population is quite diverse. “Half of the people who come to Topaz are from Brussels,” says Distelmans. “French, Dutch, English, Arabic – we hear a bit of everything.”

In Brussels itself, ADMD offers complete information on euthanasia and palliative care options in French.

About the author

Lisa Bradshaw is the editor-in-chief of Flanders Today, The Bulletin’s sister publication, and a daily contributor to The Bulletin. She also contributes to Ackroyd Publications’ other titles, including WAB and Expat Time. She has worked as an editor, proofreader and writer for other publications and organisations in Belgium and the UK, including Flanders Audiovisual Fund, Metropolitan, European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy and Ghent University. Previous to her arrival in Belgium, she served as the arts editor for an alternative weekly in the US.