- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Covid causes rare outbreak of unity in Belgian politics

Belgium has become a byword for contorted political solutions, the result of its many layers of government pulling in different directions. But the country’s response to the coronavirus has involved something surprising: a single, national approach.

“There were absurd, typically Belgian situations in some other federal countries, but we didn’t really have them in Belgium,” observes Dave Sinardet, professor of political science at Vrije Universitet Brussel.

United we stand

From the lockdown in March through to the curfew and the closure of cafes, bars and restaurants in October, measures have largely been decided for the whole country, regardless of region or language. This has even occurred with education and for the most part with culture, areas which are jealously guarded by Belgium’s different language communities.

For example, even though the ministers for French- and Dutch-language education disagreed going into the lockdown, they reached a compromise and the schools were closed across the country. And in October, restaurants everywhere were closed despite resistance from both the Flemish and Walloon governments.

“That’s quite surprising,” Sinardet says. “In Belgium, the typical idea is that when politicians don’t agree, they should just use their autonomy and do their own thing.”

In part, this may be down to Brussels, where diverging policies would have created glaring and possibly dangerous contradictions, such as Dutch-speaking schools staying open while French-speaking schools closed. But there has also been a strong sense of pragmatism. “There seems to be a general feeling that corona politics is not something to play games with, although there have been some exceptions.”

These included the latest round of closures in the sport, culture and event sector towards the end of October. There was an initial lack of unity in the three regions as Brussels was the first to clamp down before successively Flanders and Wallonia. But the federal government reasserted itself at the end of October to conclude a unified national lockdown.

Belgium’s response to the coronavirus has benefited from the established system of disaster planning. “Preparing hospitals for a large inflow of patients started early on and was pretty well organised, and so the hospitals were able to cope,” says Steven Van de Walle, professor of public management at KU Leuven’s Institute of Public Governance.

In particular this involved Belgium’s provinces, the level of local government below the regions. “There is a lot of debate about whether we should still have provinces and provincial governors in Belgium, but one of their remaining tasks is coordination in case of disasters or epidemics, and they took up that role.”

It was down to the provincial governors, for example, to arrange overflow facilities in suitable vacant medical centres, care homes or hotels, in case the hospitals reached capacity. In the event, intensive care capacity across the country proved more than sufficient to meet the demands of coronavirus cases during the first wave.

Belgium also benefited from having a mechanism for temporary unemployment already in place. “Faced with the closure of restaurants, cafes and shops during lockdown we could use this tool to alleviate the situation, both for workers and employers,” Sinardet says.

Divided we fall

These positive aspects of Belgium’s response to the coronavirus do not mean that everything went well. “What went badly was ownership of the crisis management,” says Van de Walle. “Different levels of government were constantly taking initiatives against each other and there was very little unity in communication.”

For example, statements by Belgian prime minister Sophie Wilmès in her weekly press conferences would be immediately contradicted by the regional leaders. “That had to do with distrust between the different levels of government, and politicians trying to attract attention to their own activities rather than giving credit to other levels, or other politicians.”

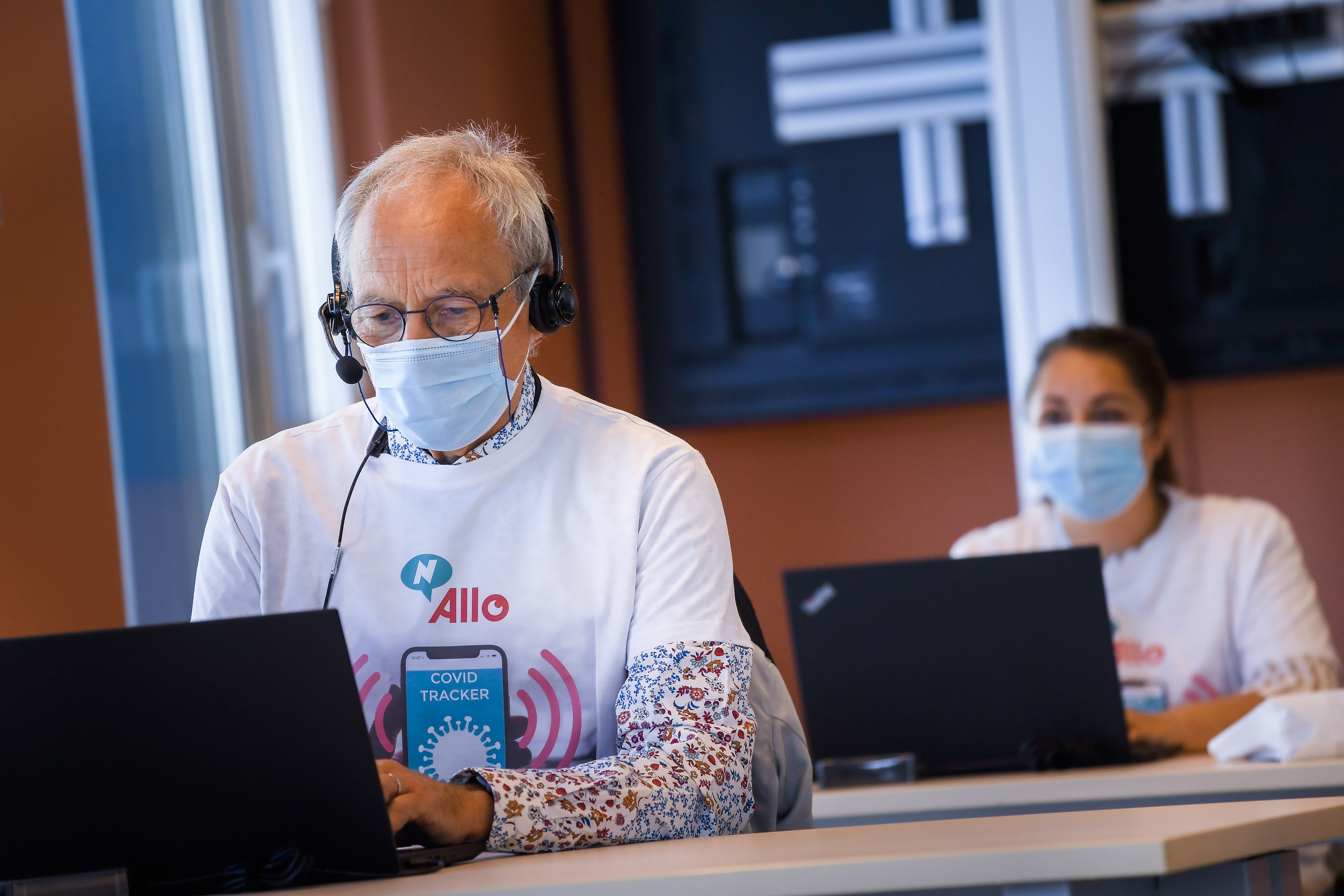

Contact tracing was one issue where everyone agreed there should be a unified approach, but no one appeared prepared to accept responsibility. “Discussions went on for about a month,” Sinardet recalls, “with the federal level saying that the communities should do it, and the communities saying it was for the federal level. In the end no one did it, and so contract tracing started later.”

Even then, implementation left a lot to be desired, with information about returning travellers and visitors to restaurants and cafes collected but scarcely used. “We still don’t know where most infections happen, and there is no scientific data to back up decisions such as closing cafes and restaurants.”

Then there were the residential care homes, which experienced alarming infection rates and severe shortages of personal protective equipment for staff. “At the beginning of the crisis, it looked as if the politicians had forgotten that we have care homes,” says Van de Walle. “They caught up eventually, but it took a while, and only happened after a lot of media attention.”

Facing the second wave

The response to the second wave of the pandemic has been marked by the formation of a new federal government. Although Wilmès’ administration was given full powers to act for the first six months of the pandemic, it remained a caretaker government.

“Constitutionally it was a government with full powers, but in practice the political engagement only related to corona, the coalition only involved three parties, and so it didn’t necessarily have the legitimacy or the dynamism to make stronger decisions,” says Sinardet.

Alexander De Croo’s incoming government feels different. “The current federal minister of social affairs and healthcare [Frank Vandenbroucke] is better placed than his predecessor, and has a bit more legitimacy,” says Sinardet. He also polls well. “After just one week, he was the second most popular Flemish politician, so there is strong support from public opinion.” Vandenbroucke’s comments on Belgium’s rising contamination figures in October made international headlines when he said the country was the worst affected region in Europe and warned that “we are really close to a tsunami … that we no longer control what is happening”.

New Covid commissioner Pedro Facon’s ensuing response was that the worsening situation was “worrying”, rather than “desperate”. His appointment to coordinate health policy between the different levels of government was one of De Croo’s first decisions. Wilmès could have done this, following the model of the commissioner appointed during previous animal flu pandemics, but she chose instead to work with what she had.

“Specific members of the government were given specific tasks in the response, mainly state secretary Philippe De Backer, who became a kind of de facto commissioner,” says Van de Walle.

Having a Covid commissioner in plain sight should make coordination more effective, although the task will not be easy. More will be asked of the regions in this phase of the crisis, for example when it comes to the economy and schools, and greater demands are likely on individual cities experiencing high infection levels.

“So it remains to be seen if the Covid commissioner can coordinate all their efforts, or if we will end up with a cacophony of measures across the territory,” Van de Walle concludes.

About the author

Ian Mundell is a British freelance journalist based in Brussels, covering current affairs and culture in Belgium and beyond.

This article appears in The Bulletin's online magazine