- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Standing room only: Brussels exhibition tells story of public urinals

In further proof that Brussels’ cultural scene is nothing but varied, an exhibition themed around public urinals is coming to the city later this month.

After runs in Berlin and Paris, LaVallée in Molenbeek presents the exhibition Cottages: Public Toilets, Private Affairs by French photographer/videographer Marc Martin, who describes himself as “one who explores the visibility of sexual minorities and claims a freedom to express – explicit or not – a diversity of practices”.

“By confronting the notions of beauty and repulsion, of good and bad taste, I readjust the level of tolerance, including of the LGBTQI community,” he says.

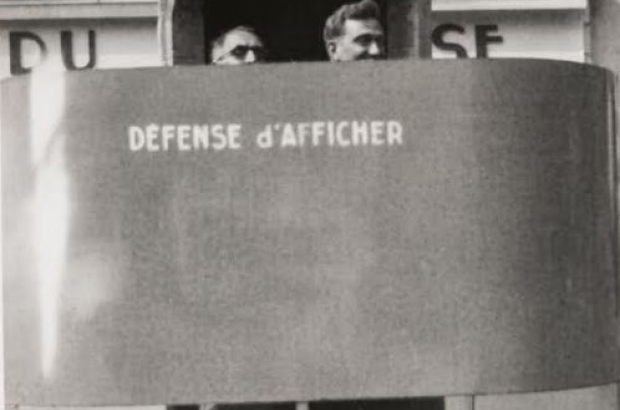

In the exhibition, Martin combines vintage photographs of the 19th century, by anonymous photographers that he found in flea markets and garage sales, with a photo novel he shot in the Art Nouveau setting of the non-operational toilets of the Palais-Royal metro station in Paris.

The public urinal was developed in 1834 in Paris and euphemistically called vespasienne after the Roman emperor Vespasian, who decided to tax urine. Urinals were a necessary step forward in public hygiene in the increasingly populated cities of 19th-century Europe.

In Brussels, the sanitary facilities were still rudimentary. A large proportion of the houses had no latrines. Where toilet facilities did exist, there was often no maintenance. The inhabitants relieved themselves wherever and whenever: among other places, under the shelter of a tree, in dark corners or against discreet walls. Some of the alleys witnessing wild peeing were given nicknames by the citizens of Brussels such as Pisstrotje.

In 1845, the first public urinals were built in Brussels and the authorities started to enforce the 1836 law against public urination. This immediately caused the circulation of cartoons of the Manneken Pis being arrested.

Very soon, urinals became infamous as cruising spots for homosexuals, faire les tasses (tearooming) in French, and cottaging across the Channel. The three-stall vespassienne became a cruising favorite, the middle stall being so “practical”.

“Urinals have always had a bad reputation,” says Martin. “They are more synonymous with shame than pride within the LGBTQI+ community. Those who flirt in there have often been accused of being cowardly; their encounters in these public places described as sordid.

“But didn't they, for over a century, dare to confront pleasures that were forbidden by the law? I wish these men could be credited with a certain braveness.”

The show also delves into the movement for gender equality that developed with the creation of the public urinals. Public facilities were built exclusively for men, the city planners believing that women would not urinate outside of the home. Eventually, a few mixed structures were built, but were staffed, fee-paying places, built in parks and department stores.

There is also a section of the show devoted to the Madames Pipi (loo ladies), the usually elderly women who keep public toilets clean.

The exhibition is organised by LaVallée-Smart in collaboration with the Schwules Museum and Rainbow House Brussels (as part of the Pride Festival).

18 September-3 October, free