- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

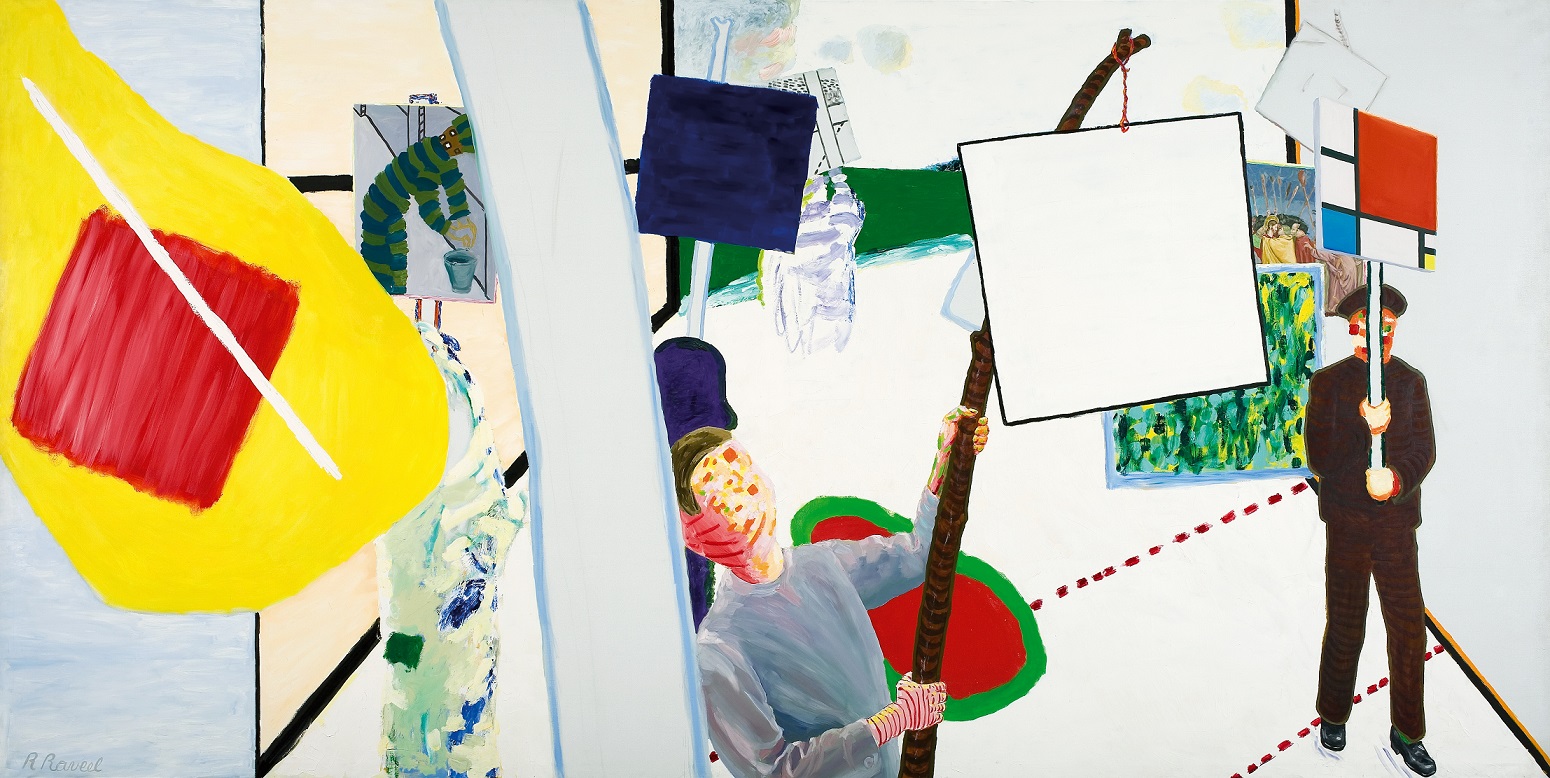

Spotting Raveel: Retrospective of Belgian artist who broke with all conventions

You might know an Ensor or Bruegel when you see it, but would you know a Raveel? “If you see a man with broad stripes along his body, that’s a Raveel. If you see a figure in a garden with a kind of Mondrian-like pattern on his head, that’s a Raveel.”

Franz Wilhelm Kaiser certainly knows a Raveel when he sees it. He curated the Roger Raveel retrospective opening this week at Bozar in Brussels. His above reference is to Piet Mondrian, the turn-of-the-20th-century Dutch artist well known for his abstract square patterns in bright blues, reds and yellows.

Raveel, who died in 2013, used this same colour pallet in his paintings, a mixture of abstract and figurative that saw him breaking with the conventions of his day. The exhibition in Bozar contains 150 works by Raveel in his prolific career spanning 70 years.

Raveel began painting in the 1930s in his hometown of Machelen, a village in East Flanders. It was in the late 1940s that he really began to forge his own path and become known for his individualistic style. Finding his stride, he even famous destroyed everything he had painted before 1948.

“From the very beginning, he was systematically rejecting the mainstream of the avant-garde,” says Kaiser. “That was abstract, and he decided not to be abstract. He is a painter between abstraction and realism. It’s a very specific type of work.”

He also never left Machelen, finding there were plenty of subjects in this rural village to inspire his massive oeuvre. “Raveel stuck to the village where he was born. He did not go international, which was always a major ambition for artists in the 1950s.”

In the avant-garde movement, explains Kaiser, “artists travelled from the city to the countryside to find ‘the simple life’, like the origins, their roots. Raveel had a completely different approach. He looked for signs of modernism, modern technology in the countryside, the effects of the modern world on rural areas.”

And he represented these tools in the same way he did the people – with geometric shapes, bright colours and broad strokes of paint that offer a two-dimensional perspective. “For him, one of the signs of modern times was concrete,” says Kaiser. “He painted walls and pillars over and over again. You can find them all over his work.”

In the pivotal year – 1948 – he introduced these colours that are detached from realism, similar to the Fauvists. “That’s really the start of his own style,” says Kaiser. “Yellow becomes very important when he invents the man with his stripes. He models the plasticity of the body.”

He had formed a ‘signature style’, a term coined in 1950s New York. “You can see in the exhibition how he developed these elements. They came out of a purely painterly problem that he had to solve. And he came to a solution that is completely Raveel. After that, he used it as a signature style.”

Kaiser is German, previously the director of the Bucerius Kunst Forum in Hamburg and now based in Den Haag, where he is soon to take over the reins of the Karel Appel Foundation. He once curated a temporary exhibition at the Roger Raveel Museum in Machelen, where he met Raveel.

“You can immediately see that he’s a guy from the countryside,” Kaiser says, laughing. “Of course with his cap and his colourful suit, he’s a little more artistic, but you can still that he’s at home in village life.”

While the Roger Raveel Museum is a great spot to learn about the man’s work, it’s inconveniently located for a majority of Belgian residents, not to mention tourists. It is hoped that a major exhibition in Bozar will introduce Raveel to more of an international audience.

“He’s known in Belgium and the Netherlands, and that’s about it,” says Kaiser. “I think it’s a language thing. There is a lot of literature on Raveel, but it’s all in Dutch. We wanted to have this show travel internationally, but we always got the reaction: ‘What nice work! But I never heard of him.’ So there has to be an intermediate step. We have published a very nice catalogue in English, with highlights in French and Dutch. It’s the first comprehensive publication in three languages about Raveel.”

The retrospective in Bozar – staged in celebration of what would have been Raveel’s 100th birthday – also contains many works that have been borrowed from other museums and private collections across Belgium and the Netherlands. “There are some late works from the museum in Ostend, including a huge painting from their courtyard, five metres wide. It’s not very well known, but it is spectacular. We put it at the very end of the exhibition.”

Roger Raveel: A Retrospective, 18 March to 21 July, Bozar, Rue Ravenstein 23, Brussels

Photos, from top: ‘Man with Wire in Garden’, 1952-53, ©Flemish Community Collection & Roger Raveel Museum; ‘Yellow Man with Cart’, 1952, ©Flemish Community Collection & Roger Raveel Museum; ‘The Paintings Parade, 1978, ©Arnhem Museum; ‘Woman with Fine Mirror’, 1953, ©Roger Raveel Museum