- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Small lab in Wallonia provides healing animal venom to companies around the world

Companies and researchers all over the world are increasingly interested in using toxins from animal venom to produce medicine. A small lab with unique expertise, tucked away in the village of Montroeul-au-Bois, Hainaut, provides them with venom from the most diverse animal species.

It sounds paradoxical: using often deadly venom to create products to improve people’s health. But researchers found that the toxins in venom affect the health of prey via similar mechanisms to those that need to be adjusted in people to cure them from diseases. The essential components are specific molecules called peptides.

Pharmaceutical companies have already used toxins to develop painkillers and medicine to treat conditions such as cancer, diabetes, obesity and heart failure. Diagnostic tools based on this material, for example to detect brain tumours, are in the pipeline. The cosmetic sector also uses it, to create new kinds of anti-wrinkle creams.

To obtain the necessary toxins, many companies and researchers are coming to Wallonia’s Alphabiotoxine Laboratory, founded by Rudy Fourmy about 10 years ago. Fourmy’s career path is remarkable: he gained a biotechnology diploma and started his career at the French lab Latoxan –also producing venoms – but he then worked for more than 20 years as a driving instructor before establishing Alphabiotoxine in 2009. Two years ago he put the company in the hands of a new director but is still involved closely in its working.

The Walloon company is part of an exclusive club. “There are only two other professional venom-producing labs in Europe and maybe fifteen globally,” says Fourmy. “We also stand out with the diversity of our toxins.”

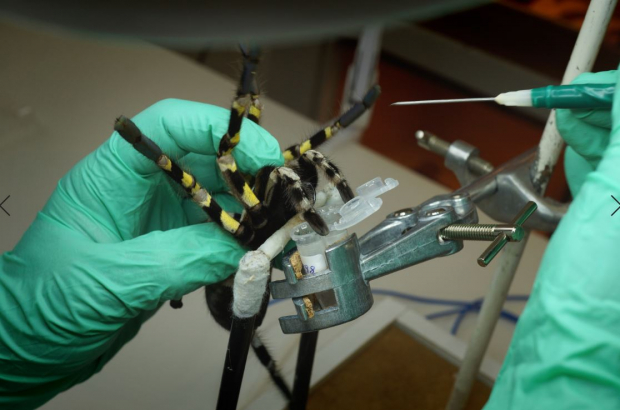

While most of its competitors focus on snakes and scorpions, which are the easiest to handle for this purpose, Alphabiotoxine houses a large variety of species in its facilities: many varieties of spiders, bees, centipedes, sea anemones, sea urchins, sea slugs and more. In total, the company has a catalogue of about 300 toxins. Alphabiotoxine exports mainly to European countries but has clients all over the world, including in the US and Asia.

Extracting venom from snakes is relatively simple if you know how – and are not afraid – to treat them: pressing their venom glands causes the poisonous substance to run out. Scorpions are a bit more complicated, requiring electrical stimulation. But how do you manage it with complicated creatures such as miniature spiders or sea urchins? “That’s a business secret, of course,” says Fourmy. “That’s one way in which we make the difference.”

The venomous animals are not like cows that can be milked every day. Snake venom can be tapped frequently, that of scorpions quite regularly, but some species can only provide it a few times a year. That’s an important factor in the high cost of certain venoms, with prices higher than €100,000 a gram. “But it’s generally bought in milligrams, so we don’t get rich doing this work,” says Fourmy. The company employs only one person full-time – director Aude Violette – and otherwise works with external technicians.

Alphabiotoxine also sells its expertise. “We increasingly provide consultancy services as well, assisting companies and researchers to use the toxins in the correct manner,” says Fourmy. “While the interest in our domain has grown, there is still a lack of experience.”

An important project that stimulated this sector was the European Union’s Venomics project, which ran from 2011 to 2015. Alphabiotoxine provided the venom for Venomics, which was used by knowledge centres and companies to set up a database of about 25,000 molecules extracted from 200 venomous species. “Tests with these molecules are now under way,” says Fourmy. “I expect several new medicines based on these toxins in a decade.” This research is not only for the benefit of people, but also for that of certain venomous animals. “Many venomous species are endangered,” says Fourmy. “The interest in them for healthcare purposes can indirectly help to safeguard them.”

This article was first published in the Wab magazine

Comments

"The company employs only one person full-time."

Strangely, all the other employees seem to disappear after a few minutes on the job. Nobody understands why... ;)