- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Manuscripts of Irish friars in 17th-century Leuven digitised

A remarkable collection of manuscripts assembled by Irish friars living in Leuven in the 17th century has been reunited, thanks to an international digitisation project. The whole collection is now available online for scholars to study, and to inspire anyone interested in Irish history and literature.

Leuven was an important place for the Irish diaspora in the 1600s. Four Irish colleges were established in the city, attracted by the prestige of the Catholic university. Hundreds of seminarians came to study for the priesthood when it was forbidden by the Protestant authorities in Ireland.

St Anthony’s College of the Irish Franciscans was particularly powerful. “It was the mother college of the Franciscans, with special powers to forgive those who had sinned,” explains Hedwig Schwall, director of the Leuven Centre for Irish Studies.

12-year mission

The Irish Studies centre is a kind of secular successor to St Anthony’s College. A part of KU Leuven, it is based in the College buildings on Janseniusstraat and co-ordinates the European Federation of Associations and Centres of Irish Studies. “We are still a hub, a kind of mother house for all the other centres of Irish studies around Europe.

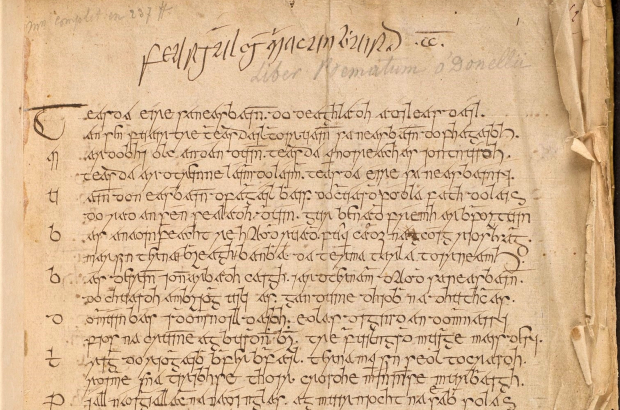

Founded in 1607, St Anthony’s College built up a substantial library, sending one of its friars, Mícheál Ó Cléirigh, to Ireland to collect and copy manuscripts. He spent 12 years on this mission, collaborating with local scholars and gradually sending material back to Leuven.

Written mainly in Irish, these manuscripts included religious and secular histories, accounts of the lives of the saints, and religious and bardic poetry. Some contained information compiled for the first time, while others were copies of originals that were later lost or destroyed. In many ways it became a unique collection.

But storm clouds gathered with the French Revolution, and the arrival of French troops in Leuven. The College was closed in 1794, and the manuscripts were dispersed among safer Franciscan houses.

Many ultimately made their way to Ireland, where they form part of the collection at University College Dublin. Others ended up in the Royal Library of Belgium.

With the Dublin manuscripts being digitised as part of the Irish Script on Screen project, Leuven started to think about doing the same for those in the Royal Library. “As well as helping conservation, digitisation is a great way of democratising rare sources, giving access to them on a huge scale,” says Mel Collier, KU Leuven’s chief librarian. “We also liked the idea of virtually reuniting the Belgian manuscripts with those in Dublin.”

Funding was secured through the Irish Embassy in Belgium and the work entrusted to the digitisation service of KU Leuven Library. As luck would have it, the team was already working in the Royal Library when the green light came, scanning graphic works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. “This is why we were able to quickly digitise these 13 manuscripts,” says Bruno Vandermeulen, head of digitisation and document delivery.

Quickly is relative, however. Each manuscript is a bound collection of documents, written on paper or parchment, which has to be handled very carefully.

“Digitisation is very manual,” says Vandermeulen. “You have to turn each and every page. You only capture one page at a time, because you can’t open the volumes 180 degrees. It’s not safe for the binding.”

It takes two people to do this properly, while a third records page information as metadata attached to each image file. The whole project took a month and produced 5,000 high-resolution images.

“We take pride in what we do, and we have a focus on quality,” says Vandermeulen. “That means handling the material in the safest possible way, but also the quality of reproduction, colour accuracy, contrast and so on.”

'Very colourful'

This is done to an international standard, so that when the images of the manuscripts from Brussels and Dublin are seen together in the virtual space of Irish Script on Screen, it’s as if they are still side by side in St Anthony’s College, Leuven.

While the manuscripts are clearly of interest to historians, they also speak to scholars of Irish culture more broadly. “There is a lot of religious material, and it is very colourful,” says Schwall. Her own interest is in Irish literature, which leads her to single out a poem on the Lough Derg pilgrimage.

“That’s the one I would like to see translated,” she says. “Lough Derg is a pilgrimage of extreme asceticism, and lots of short story writers from the 19th century to the present refer to it. So you would want to know how it was seen by someone in the 17th century.”

This article first appeared in Flanders Today