- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Goya and Spanish Realism: Europalia exhibition explores light and shade defining the nation’s identity

Europalia’s flagship exhibition Luz y Sombra: Goya and Spanish Realism at Bozar shines a light on the legacy of the pivotal Spanish artist Francisco de Goya.

This ambitious show explores the light and shade at the heart of Spanish culture and society, the two intertwined strands serving equally as thematic for Europalia España’s multidisciplinary arts programme running across Belgium until 1 February.

In dialogue with the 74 paintings and prints by Goya (1746-1828) are 150 multimedia works by his contemporaries and artists of later generations, including José Gutiérrez Solana, Pablo Picasso and Antonio Saura.

This juxtaposition with around 70 Spanish artists illustrates how the revolutionary art figure’s complex and nuanced oeuvre has influenced not only the art world, but the identity of his nation. “We show how his ideas, techniques and themes persist in Spanish art from the 18th century to the present day,” explains curator Rocío Gracia Ipiña.

“His approach is modern because he constantly experimented, merging form and content,” adds co-curator Leticia Sastre Sánchez. “This makes him relevant to many contemporary artists who, like him, are seeking ways to understand and represent reality.”

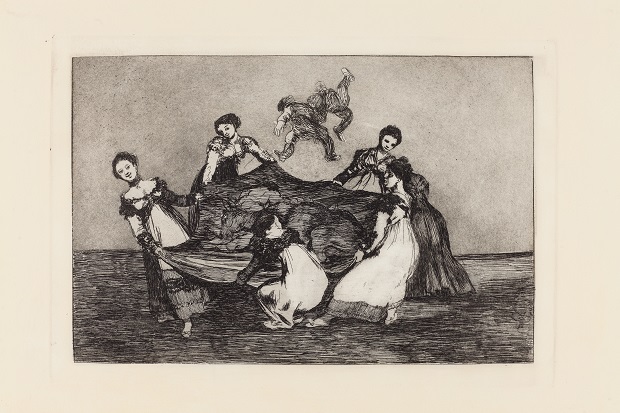

While the exhibition includes some of Goya’s iconic works, such as his graphic series Disasters of War, his most famous works are absent. It nevertheless succeeds in presenting both his work and his legacy in a fresh light. The grandmaster was partly responsible for the contrasting stereotypes that persist around the notion of ‘Spanishness’, with his early colourful tapestry cartoons created for palace interiors appearing to contradict his later satiric and darker depictions of society.

This is in part due to the turbulent age through which Goya lived: the rise and fall of reason to the Napoleonic war and his own personal sufferings. Originally a country boy from the region of Aragon who rose to the lofty position of court painter, he remained a man of the people, yet one who incisively portrayed the foibles and follies of society in his macabre ‘black paintings’. This versatility and his rarified position of being one of the last old masters and first truly modern artist has only heightened his reputation.

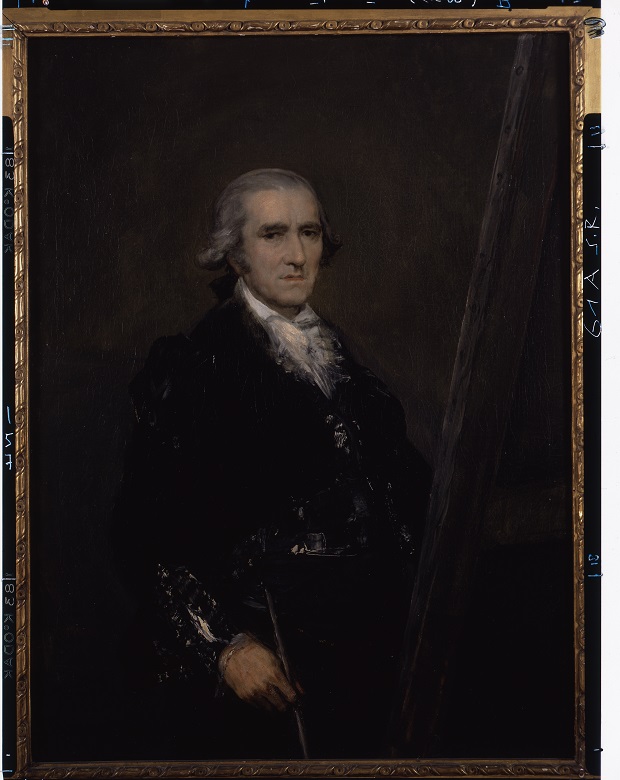

At the entrance to the exhibition, a timeline filled with captivating details and images of his life in Spain and France is testament to Goya’s prolific career and legacy. The show is divided into three chapters; the first dedicated to the artist’s Baroque and classicism period. It’s an immediate immersion in his life as a royal portraitist with luminous large-scale paintings revealing his classical art training, shown alongside works by his contemporaries.

Travel to Italy early in his career further broadened his artistic vocabulary. Already, he was mastering brushwork, pursuing naturalism and paying careful attention to light. An audacious approach to experimentation also fuelled his career and influence. The second section explores Goya’s portraits during the period of Enlightenment, when he captured the individuality of notable figures with a dedication that surpassed the norms of the age.

He similarly delved into portraying of popular culture with bold, evocative imagery to create joyful scenes with a trademark empathetic gaze. The enduring influence of Goya is illustrated in the numerous copies of his work, while sculptures, tapestry and colourful ceramics attest to the place of craft industries in the 18th century and their subsequent revival in the 20th century.

In the early 1790s, illness left him completely deaf, which probably further darkened his outlook on the world. The Los Caprichos series of prints, published in 1799, are an example of Goya’s critique of Spain’s struggle with the clash between Enlightenment ideals and engrained social hierarchies and religious dogma. The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (pictured above) graphically warns of the perils of abandoning reason. In these etchings and engravings, Goya used the grotesque to illustrate his themes: witches, demons and goblins acted as metaphors for violence, ignorance and blind superstition. “Everything human is in the work of Goya,” reminds Leticia Sastre Sánchez.

The final chapter of the exhibition turns to Goya’s considerable influence on expressionism and abstraction. It includes the Disasters of War series that depicts Napoleon’s invasion of Spain; the realist master was an inspiration for other artists reacting to similar conflicts and historic events. There are also works of pagan celebrations such as carnival contrasting with the deeply-embedded tradition of Holy Week that follows the popular event.

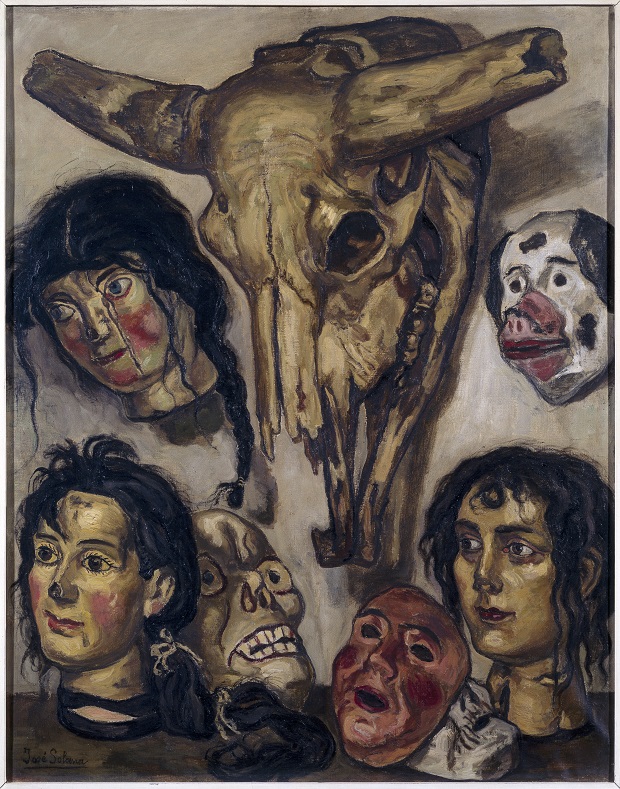

The dual visage of life and death is another major theme. A thread of cruelty runs though Picasso’s still lifes and José Gutiérrez Solano’s enigmatic Cabezas y caretas (1943, pictured above) that illustrate the poised link between the two. This tension pervades a series of works by Goya and subsequent painters, including Picasso and Pop artist, that portray the timeless duel between the bull and the bullfighter and capturing the ritualised movements of the practice.

Specially commissioned for the exhibition are two audiovisual works: Tauromaquia by filmmaker Albert Serra and the riveting installation Cordero Social (Social Lamb) by Álvaro Perdices. The latter is a four-camera live video broadcast from the interior of a Madrid church that takes viewers inside the popular meeting place with visitors queueing for coffee next to Goya's last religious work (pictured below).

The show is a rich and profound exploration of realism and its role at the heart of Spanish identity. Its focus on light and shade creates a pertinent dialogue between the past and the present, the weight of tradition and modern innovation. This complex reflection is equally relevant for the reality of our own times.

An extensive multidisciplinary programme surrounds the exhibition. It is also accompanied by a detailed illustrated book in English, published by Pelckmans in collaboration with Europalia.

Luz y Sombra: Goya and Spanish Realism

Until 11 January

Bozar

Rue Ravenstein

Brussels

Photos: (main image) Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, extract from Las mozas del cántaro 1791–1792 ©Archivo Fotográfico. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid; Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, Disparate femenino, serie Disparates no 1 ©Fundación Ibercaja, Zaragoza; Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, The sleep of reason produces monsters (No. 43) from Los Caprichos ©Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando; José Gutiérrez Solana, Cabezas y caretas ca. 1943 ©Archivo Fotográfico Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía; Cordero Social (Social Lamb) by Álvaro Perdice