- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Darkness into light: Treating depression with virtual reality

How would you like to meet with your therapist as an avatar in a virtual world? It could become a reality if a research project by a group of Belgian psychologists and creative technicians proves successful.

It’s called Soulhacker, and the group is the first to develop such a virtual reality (VR) programme for the treatment of depression. Already in the works for a couple of years, collaborators have made great strides in refining Soulhacker’s technology and the approach.

The basic theory is that people suffering from depression and anxiety cannot see things differently. But if you show them how their own simple actions can alter their surroundings, they begin to see a glimmer of hope for the future. They can create change in a virtual world, if not yet in the real one.

“For depressed people, the world is very black,” says Georges Otte, one of the psychiatrists behind Soulhacker. “It’s cold and dark, there’s no light, there’s no energy, there’s no evolution. If a patient can change that, they will experience not just the darkness and emptiness of depression but also a transition to a place of light, to a more social life.”

‘Change is possible’

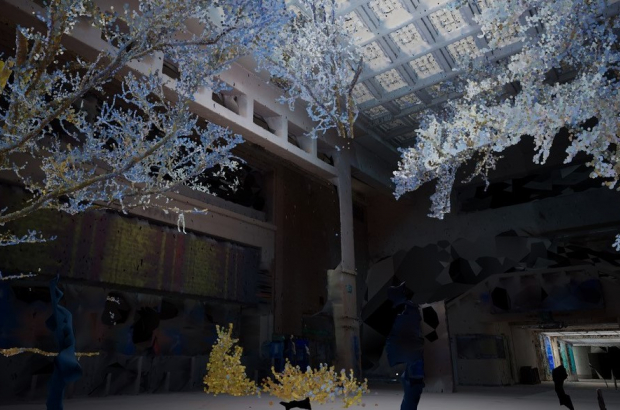

In Soulhacker’s virtual world, patients first finds themselves in a dim forest or old building. “Then the patient looks for clues to help them,” explains Otte, who is specialised in neuropsychiatry. “We have already carried out tests where we had people find green crystal balls. When the patient picks up a ball and throws it, it generates a tree of light.”

With every new tree generated, the forest becomes lighter and lighter. “The threat of the dark disappears, and the forest becomes a really pleasant place,” continues Otte. “This helps to embed the idea that change is possible. I see a lot of patients suffering from depression, and I’ve lost patients to suicide; they were convinced that nothing could save them, nothing could change them. They were beyond hope. It’s always a struggle to convince them that they can be saved. If you talk to them rationally, that doesn’t have an impact, but if they experience that change is possible, that’s another story. That’s where VR comes in.”

Otte, previously head of the Dr Guislain Psychiatric Centre in Ghent, is working on the Soulhacker project together with others from the BRAI3N research centre and clinic, also in Ghent. BRAI3N is focused on neuromodulation, a therapy that sends electrical impulses to nerves, muscles and the brain to treat specific conditions.

VR doesn’t in itself apply involve electrical impulses or indeed any physical procedure; it is focused on changing perceptions solely through visual stimuli. It has its roots in hypnosis, in fact, where metaphors stand in for a patient’s experiences.

A VR experiment that allowed two participants to see through the eyes of the other person

Eric Joris saw first-hand how powerful this effect can be through the use of VR in a cultural context. He is the director of Crew, a Brussels company that stages theatre and other visual experiences using new technologies, including VR.

“When we started in 2004 with a kind of VR – it was video based – people had very strong emotional responses,” he recalls. “Once we had a woman who was in tears at the end, and we didn’t understand why exactly because the work itself wasn’t very emotional or sentimental. She told me that she was a hypnotist and that what we were doing was very close to hypnosis.”

People tend to think of hypnosis as an old-fashioned form of entertainment, a pocket watch swung in front of someone’s face until they go out like a light. In practice, hypnotherapy involves inducing a very focused state so that a patient is more open to suggestion and the use of analogies.

Crew was surrounding its audience with video screens that made them feel not as if they were just watching but actually taking part in another reality. “We were slowly progressing the story and talking directly to the audience. People are walking around in a world that seems to be their own, but there was an actor with a very deep voice slowly talking to them. That brought on a state that is similar to hypnosis. So already on that level, you can progress with people to involve their emotions.”

Self-empathy

That was the start of a number of experiments with VR, performance and emotional response. At one point, they used VR to give someone the perspective of another person. People could actually see themselves through the eyes of the person in front of them.

“You had to operate out of the body of the other,” Joris explains. “You need empathy to control the other person’s movements, to help the other person in order to help yourself. This set-up is very complicated and a lot of work, so you can’t really produce it on a large scale, but it proved you can have a very strong impact.”

Stanford University has carried out experiments, notes Otte, into the effect of VR on empathy. One was a scene in which a patient is confronted by a prisoner in a dungeon and has to console him. “What the person said to that guy who was lying on the ground in chains was then turned around so that the patient was talking to himself,” explains Otte “The patient became very emotional, wishing that at some point in his life someone has spoken to him like that.”

While VR is currently used to treat phobias, Stanford is about as close as studies have come to examining the effect of VR on depression. “For the rest, there has not been much,” confirms Otte. “In wellness, meditation, relaxation, there’s been a lot of work carried out. But not for depression.”

Current experiments let participants walk around in real space as they do in the virtual space

BRAI3N and Crew are working on Soulhacker together with students from the RITCS Institute for Theatre, Cinema & Sound in Brussels to create virtual worlds for the study. And it’s the intention that the visuals will not be automated; they can be adapted to the patient’s emotional and biological responses.

This means that the patient is not only equipped with a VR headset but with sensors to measure heart rate, perspiration level and brain activity. This way visuals can be altered in response to the patient’s stress level or emotional state.

“The idea is that patients walk into a landscape and start changing it,” says Otte. “So we must be able to measure the emotions and even send a therapist into the virtual world in the form of an avatar. The therapist will see what images generate what emotions in the patient and can adapt them. So it will be an interactive game of therapist, patient and environment.”

Otte says that, should all go well, the therapy could be used within two years.

Photos courtesy Soulhacker