- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Coronavirus in Belgium: Behind the masks of some of the country’s frontline workers

In the first of a series reporting on Belgium’s frontline workers, the Bulletin talks to some of the people braving the Covid-19 pandemic. From treating patients, maintaining services for the public and looking after society’s most vulnerable people, these key workers are struggling to contain the virus with often limited resources.

The hospital doctor

Specialising in internal medicine in a Brussels hospital, Claire Dubois (a pseudonym) is used to working 50 hours a week, including one 24-hour shift. Since the coronavirus outbreak, holidays are cancelled and she has been assigned to Covid-19 units, working with infected patients.

“During the 24-hour shifts, I also work in the emergency room, either the strictly ‘clean’ one or the Covid one, and I am also taking care of inpatients when they get worse,” says Dubois.

She reports numerous challenges, including staying as safe as possible without proper equipment. “We are not sure we are being protected with what we are getting from this government.”

And there’s additional pressure as she “tries to be as efficient as possible to make sure people can go home as soon as possible, as safely as possible for them and their family or nursing home”.

She says: “Some of our patients are quite old, some are very young, it is troubling. We have a significant number who have died, but we also have patients who leave the hospital to go back to their families and this is just one of the best feelings.”

One difficulty specific to the epidemic, says Dubois, “is knowing who’s going to benefit from the intensive care unit. To keep the hospital from being full, we need to keep our spirit sharp and that’s not always easy because we are all getting more and more tired every day.”

She is confronted by mental as well as physical exhaustion. “It is tiring wearing masks all day, changing ourselves numerous times, trying not to make hygiene mistakes while doing so. It is even more tiring psychologically to see those patients die alone. Calling the families every day, trying to reassure them or telling them it is not getting better. Having to face the same disease every single day makes you go a little bit insane, especially when you talk only about it with your colleagues, your friends, your family, the media.”

How is she personally coping? “I think we are going to drop after the crisis from exhaustion and mental health problems. There is a dichotomy that is hard to live with, people are finally saying thank you while they were the first ones to let us down when we were in need for more recognition, more respect, more money for hospitals. It is hard not to have a bitter taste in our mouth.

“I am definitely very grateful for my family, my friends and my boyfriend who is also a doctor and who understands most of what I’m going through, even if he doesn’t live in the same reality. Sharing and being heard is delightful in these weird times.

“It might sound weird but what makes me keep on going is the idea that life is going to change for the better after all of this. I need to believe society is not going back to this consumerism, this capitalism nonsense that is directly responsible for the whole mess, otherwise it would be hard for me to fight for Covid knowing we are just going to go back to how stuff was.”

The refugee worker

When coronavirus social-distancing and stay-at-home measures were announced, Yoon Daix and his colleagues at the Citizen’s Platform for Refugee Support assumed they would have to close their shelter at Porte d’Ulysse, in Brussels.

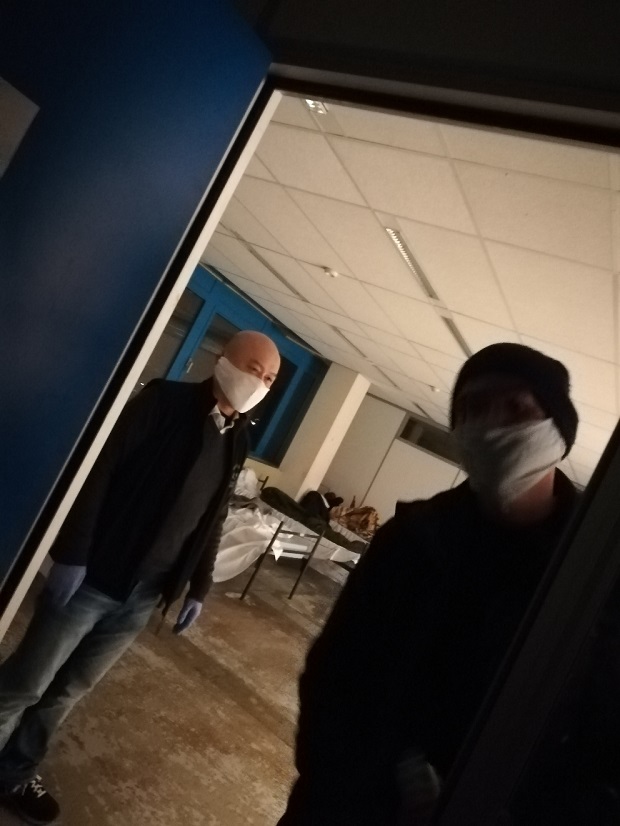

“But we realised we couldn’t send 350 people back on to the streets,” says the field officer. “As a human being, you can’t imagine doing that. We take all the precautions we can, with distancing, masks, gloves and hand-washing. We don’t have professional equipment, but a lot of people have sent us home-made masks. We serve meals in smaller groups and have reduced the overall number at the centre to 250 people, with the others being accommodated elsewhere.

Daix (pictured, left), who started as a volunteer co-ordinating the hosting of refugees in citizens’ homes, now works full-time for the platform and helps manage the smooth running of the centre. During the coronavirus crisis, it has expanded its opening hours to 24/7, to ensure the residents can stay inside all day.

“This has increased the workload, of course. A lot of our experienced volunteers were aged 65+, so we had to recruit more. Luckily, we managed to attract a lot of enthusiastic young people with spare time.

“We’ve had some suspected Covid-19 cases, but we’ve not had any confirmations. I myself was at home for a week. I’ll never know if it was coronavirus. Our biggest fear is if we get a really big infection. My family and friends worry about me and some have encouraged me to stop.

“One of the other big challenges ahead is boredom. We have 250 guys with a limited chance to go out and limited internet. When you are already in transit in Belgium and then you’re stuck, it’s horrible.”

The Red Cross volunteer

Cailin Mackenzie does a weekly 14-hour night shift for the Red Cross’s Leuven-based ‘corona’ ambulance. Patients are transferred to hospital who have confirmed or suspected Covid-19 and have developed breathing problems, and/or have an underlying condition like cancer. She and her partner wear disposal lab coats, goggles, FFP2 masks and gloves, and carry surgical masks and gloves for patients.

“I chose the corona shifts,” she says. “You don’t need to see many patients to realise how dangerous it is. It develops fast. I understand why some people aren’t realising how ill they are. I’ve seen people who can still walk and talk but their oxygen levels are very, very low. It’s not obvious, and that’s where it gets scary.

“I’m not scared about getting it. I have to stay healthy to keep doing this work. We are extremely careful. The post-shift decontamination is as exhausting as the job itself. We spend up to an hour disinfecting the ambulance and then ourselves. After the last shift we commented on how drained we were. There’s not a moment when you’re with a patient that you’re not concentrating like you’ve never concentrated in your life. You don’t realise the tension you’re holding.”

Trained in emergency medical assistance, Mackenzie – who has volunteered with the Red Cross for more than 20 years – works for the Brussels Diplomatic Academy at the VUB, including lecturing in law.

“I have relatives on the NHS frontline, in Scotland. They don’t worry about me too much. I was a responder after the Brussels terror attacks and I lived in the Middle East during the second intifada – they know I personally don’t take risks.”

Photos: Didier Lebrun/Belga, Nicolas Materlinck/Belga, Nicolas Materlinck/Belga