- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

The big gamble: art dealer Xavier Hufkens

In art as in love, it’s best to commit slowly, says Xavier Hufkens. With this interview, we profile Belgium's most successful contemporary art dealer.

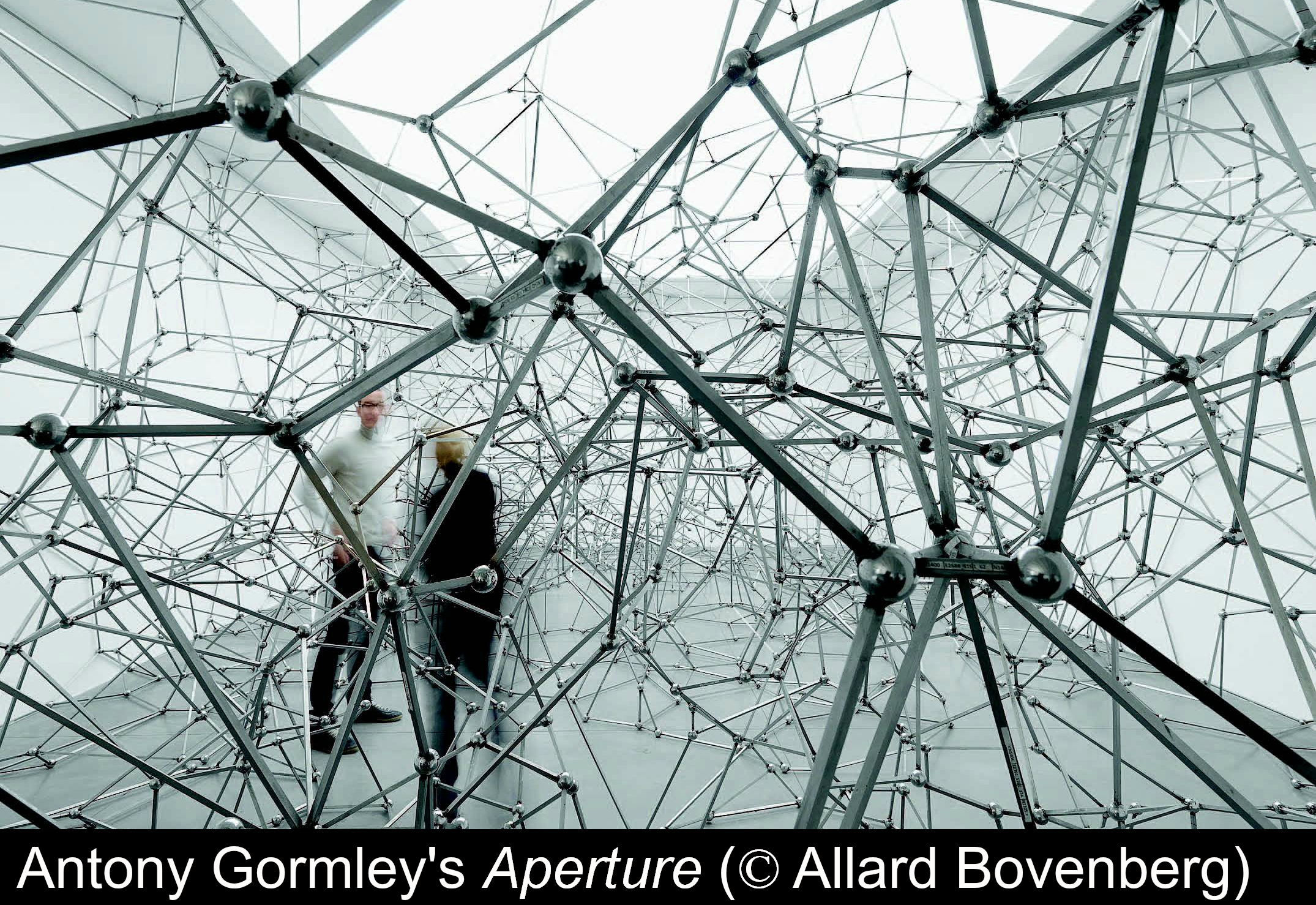

Xavier Hufkens got off to what seemed like a modest start when he opened his first gallery in an unrefurbished industrial building in Saint-Gilles. The year was 1987, and the fledgling dealer just 22. His sensibility was, as it has remained, all over the map, but he had a sixth sense for ‘quality’, a word he still uses to define his gallery’s artistic programme, and his perspective was international from the get-go. He showed, among others, then-emerging American artists Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Jessica Stockholder, British sculptor Antony Gormley, who is still affiliated with the gallery, and Lili Dujourie, a Belgian whose reputation was already well established in this country.

Five years later, Hufkens moved to an Ixelles townhouse remodelled for his purposes by architects Paul Robbrecht, Hilde Daem (renovators of Brussels’ Cinematek and London’s Whitechapel Gallery) and Marie-José Van Hee. Big names added to the gallery’s roster of artists included Arte Povera exponent Michelangelo Pistoletto and US sculptor Richard Artschwager. In 1997, after 10 years in business, Hufkens annexed the adjacent building.

Fifteen years on, Hufkens is a major player in the art world. He is on the six-member selection committee for Art Basel, the top international contemporary art fair, where this year 1,200 galleries applied for 267 available spots. He has partnerships with high-flying dealers such as Larry Gagosian in representing the estates of Louise Bourgeois, Willem de Kooning and Robert Mapplethorpe, and his stable of 39 blue chip artists and his handsome ‘house’, as he calls his gallery – arguably the most imposing in Brussels – puts him in a league apart from all but one or two of the city’s other commercial galleries. In June 2010, he sold a work on paper by Louise Bourgeois for over $650,000. Imagine what her sculpture goes for. (Proceeds from sales are shared, of course, with the artist or artist’s estate.)

But putting on exhibitions can be expensive. “When we set up a show, it’s the Cirque Bouglione,” Hufkens says. And the cost, often underwritten by the gallery, of fabricating works, can be high. While there is no guarantee that the art will sell, it is not uncommon for collectors to line up when demand for a prized artist’s production outpaces supply. The Belgian artist Thierry De Cordier, who completes two paintings a year, according to Hufkens, may be a case in point. But even when a show sells out, the gallery doesn’t always recoup its investment. “We sold everything from our last David Altmejd exhibition without making any money,” Hufkens admits with a smile.

Such are the risks in any business venture, perhaps, but artists and their products are not, for Hufkens, just about business. It’s unlikely that he was motivated solely by the prospect of profit when in 2005 he had the roof of the gallery removed so that Erwin Wurm’s Convertible Fat Car (Porsche), a bright red, ‘enhanced’ Porsche bulging in all directions, as if overfed, could be lowered into the ground floor for display. Or when, at the packed opening of that same show, he agreed to pose for one of the Austrian artist’s One-Minute Sculptures. The performance piece required Hufkens to stand motionless while Wurm, standing beside him, put his hand in one of Hufkens’ trouser pockets. After a minute had elapsed, Wurm removed his hand and placed it nonchalantly through the dealer’s open fly. Beet red, Hufkens held the pose for a full minute while cameras flashed at the spectacle of a dealer submitting completely to an artist’s wishes. Usually, it’s the artists who are in the hands of their dealers.

“When you want to understand the world, you can do it through many channels,” he says. “Mine, ever since I was very young, was to look at contemporary art, because it tells us about the time we’re living in. Art has to feed you, to be rich, lush. It has to have complexity. A dealer has a responsibility to show people that kind of work.

“I show artists I believe in. Malcolm Morely, the first winner of the Turner Prize, is a fuddy-duddy figurative painter, and Roni Horn, who’s a conceptual artist. I find strength in a rich programme in which quality is the rule, and not decorative ensembles. I don’t ask ‘Will my Louise Bourgeois fit with my Malcolm Morley?’. Well, it won’t, but it doesn’t need to. Isn’t a dealer’s programme a self-portrait, in a way?

“When you have an artist in your gallery, you’re committed. Cooling to work is a very painful process. It’s a divorce. It’s always difficult to say ‘I don’t love you anymore’. The way to avoid that is by making decisions slowly. I hope my track record is better than average. I’m taking a bet on the future when I take on a young artist. Still, you don’t sign on an artist expecting to work with him until his last breath.”

“We’re a company. We need to make profits,” he continues, “but we have a social responsibility, and the first is towards the local community. The gallery itself is vital. It’s the house where the exhibitions happen, the place where clients know they can find you and visitors know they’re welcome to see the art for free. If you have a strong home base, you can face the rest of the world. “I’ve thought of opening a gallery in Paris or London, but big cities are too competitive for me. If [Ernst] Beyeler [the great Swiss art dealer] could make it in Basel, why can’t I do it in Brussels?” No false modesty there.

“Belgium’s contemporary art scene was centred in Antwerp when I opened the gallery. Now Brussels’ art scene is fantastic. As a place of cultural interest, Brussels comes just after New York and London.” He gestures to the latest issue of the German magazine Monopol, whose cover story calls Brussels the new Berlin, a coveted sobriquet.

“The Magritte Museum attracted half a million visitors in the six months after it opened. Do you know what that means for an economy with twenty-two percent unemployment?

“Look at Wiels [the contemporary art centre]. It’s a miracle, a place of international standing. The exhibitions they organise travel to the biggest museums in the world. It’s putting Brussels on the map. “If you’re passionate about what you do as an art dealer, you get better as you get older. You can’t say that about a model or a tennis player.”

Xavier Hufkens, 6-8 Rue Saint-Georges, Brussels, www.xavierhufkens.com